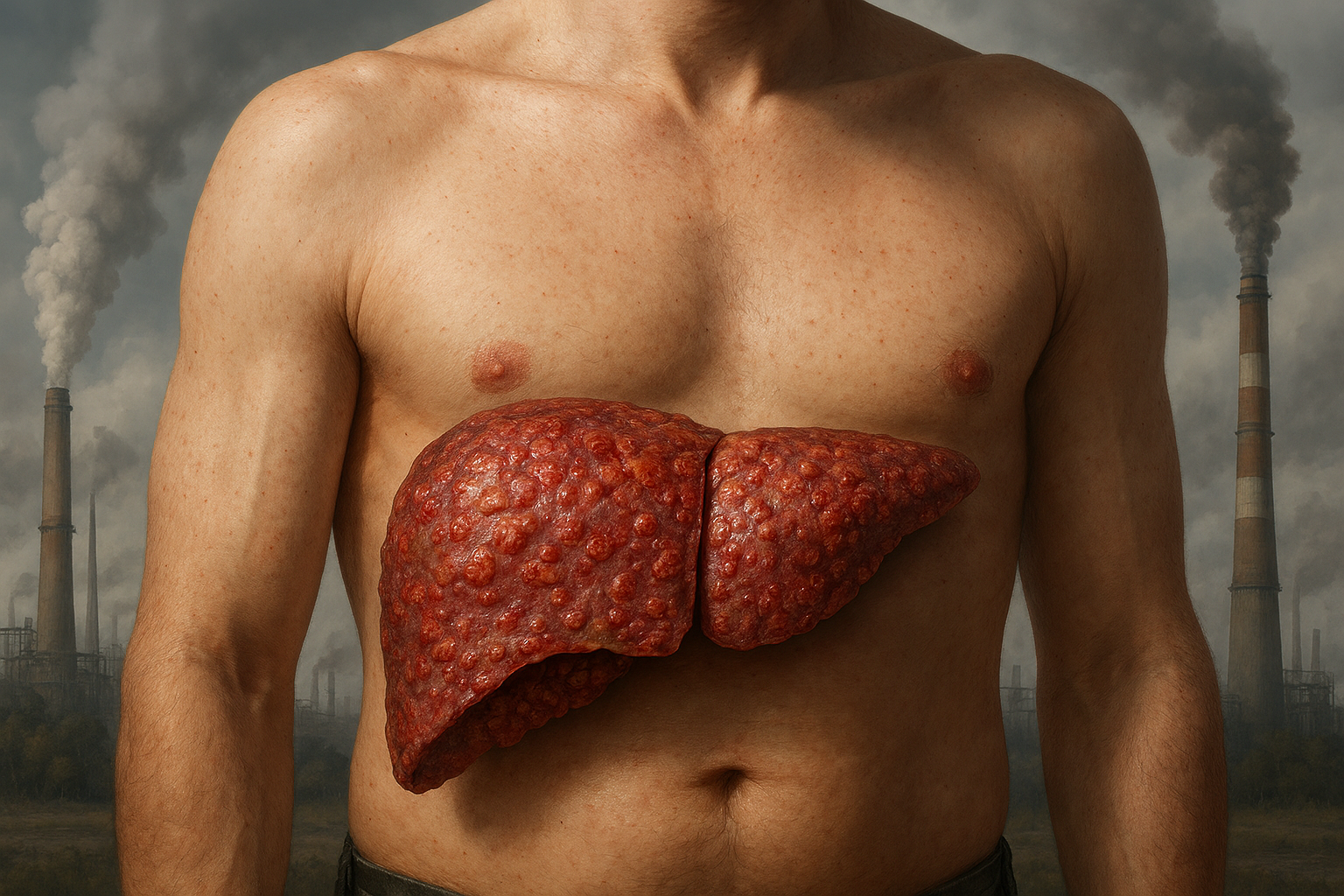

Liver Damage due to Environmental Toxins

At CLRD, we understand that many liver illnesses do not begin in hospitals or clinics, they begin in the fields, factories, and workshops where people earn their livelihoods. Over four decades, our team has documented, treated, and reversed liver injury caused by environmental toxins, especially pesticides and insecticides used by agricultural workers. Beginning with landmark observations in grape sprayers and extending to wider cohorts of insecticide applicators, we established how chronic, low‑dose exposure deranges liver biochemistry, injures hepatocytes, and advances to fibrosis if left unaddressed. Just as importantly, we transformed this knowledge into practice: early detection protocols, scientifically guided detoxification, organ support, and when necessary, regenerative therapies that restore function. The result is a patient‑centric program that does more than treat numbers on a lab report; it helps people reclaim their health, their work, and their peace of mind, with documented cures and sustained recovery in real‑world settings backed by CLRD’s published research and clinical innovation.

Liver damage from environmental toxins can manifest in several ways, depending on the type of chemical, duration of exposure, and individual susceptibility. The most common scenario involves agricultural workers who handle pesticides and insecticides. In these cases, toxins enter the body through inhalation, skin absorption, or accidental ingestion during spraying activities. Initially, the liver responds by increasing its detoxification workload, which may cause mild enzyme elevations without obvious symptoms. If exposure continues, hepatocytes begin to show structural stress, leading to fatigue, loss of appetite, and vague abdominal discomfort. This stage is often overlooked because symptoms mimic routine tiredness after work.

Another scenario occurs when exposure is intermittent but cumulative, such as seasonal spraying in vineyards or orchards. Here, the liver undergoes repeated cycles of injury and partial recovery, resulting in persistent biochemical abnormalities and early fibrotic changes over time. CLRD’s early research in grape sprayers documented this pattern, where enzyme fluctuations mirrored spraying schedules, and patients developed chronic hepatopathy if preventive measures were ignored.

A more severe scenario involves acute high-dose exposure, often due to accidental spills or improper handling of concentrated chemicals. This can precipitate sudden hepatocellular necrosis, presenting as acute hepatitis with jaundice, nausea, vomiting, and, in extreme cases, acute liver failure requiring emergency intervention. CLRD has managed such cases with intensive detoxification and, when necessary, hepatocyte transplantation as a bridge to recovery.

Certain toxins exert a cholestatic effect, impairing bile flow and causing itching, dark urine, and pale stools. This pattern is particularly challenging because it often coexists with systemic symptoms like dizziness and neurological complaints from organophosphate absorption. In some patients, especially those with pre-existing viral hepatitis or metabolic disorders, environmental toxins accelerate progression to cirrhosis, creating a compounded risk scenario that demands integrated care.

Finally, chronic low-level exposure in industrial settings such as solvents, heavy metals, or chemical fumes can lead to insidious liver injury that remains silent for years. These patients often present late, with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis discovered during unrelated health checks. CLRD addresses these complex cases through regenerative therapies, including hepatic progenitor cell transplantation, which has restored function in patients once considered candidates for liver transplantation.

Across all these scenarios, the unifying theme is that environmental toxins can harm the liver in multiple ways acute, chronic, hepatocellular, or cholestatic and the outcome depends on early recognition, timely detoxification, and advanced interventions when needed. CLRD’s decades of research and clinical innovation ensure that every patient, regardless of the stage or complexity of their condition, receives a personalized pathway to recovery.

Symptoms

People exposed to environmental hepatotoxins most notably agricultural pesticides and insecticides often present with a blend of general and liver‑specific complaints. Early on, fatigue that feels “out of proportion” to the day’s work, a persistent sense of malaise, and reduced appetite are common. As exposure continues, patients may notice right upper abdominal heaviness after meals, intermittent nausea, a metallic or bitter taste, and increased sensitivity to smells during or after spraying shifts. Sleep quality frequently deteriorates, and subtle cognitive dullness or headaches may appear after workdays with heavy exposure. Clinically, the first laboratory clues are mild elevations in alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, with or without gamma‑glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase drift; bilirubin can remain normal early on. In some patients, particularly those with cumulative exposure dyspeptic symptoms and bloating coexist, but the hallmark remains a pattern of hepatocellular stress that correlates with exposure intensity and duration, a relationship CLRD first documented in grape sprayers and subsequently among broader groups of insecticide applicators.

When injury advances, patients develop more overt features: persistent right hypochondrial pain, pruritus from cholestatic involvement, dark urine or light‑colored stools on “bad weeks,” and objective jaundice in a subset. Work‑related clustering is typical: symptoms worsen during active spraying seasons and fall back during off‑season, a rhythm that our early epidemiological and biochemical studies captured alongside enzyme fluctuations and exposure logs. Patients with pre‑existing viral hepatitis or metabolic risks can experience sharper symptom onset and steeper biochemical rises, a co‑vulnerability that informed CLRD’s integrated screening approach for concurrent liver conditions in exposed workers.

Stage-wise Progression

Environmental toxin–related liver injury progresses along a spectrum, from reversible biochemical stress to structural damage, unless the exposure is identified and mitigated.

Stage 1: Functional Disturbance (Exposure‑linked biochemical stress). In this initial phase, hepatocytes respond to xenobiotic load with inducible enzyme activity and membrane perturbation. Laboratory panels show mild aminotransferase elevation and occasional GGT rise, often normalizing with short exposure‑free intervals. CLRD’s early occupational cohorts demonstrated this oscillating pattern, where enzyme alterations tracked closely with work cycles in vineyard sprayers and insecticide applicators.

Stage 2: Subclinical Injury (Persistent enzyme elevation with cellular integrity changes). Continued exposure leads to sustained aminotransferase elevation, subtle synthetic function changes (borderline albumin decline in some), and increased oxidative stress markers. Patients remain largely functional but complain of fatigue and dyspepsia. Our longitudinal reviews highlighted that, without intervention, this “silent” window can last months to years, gradually narrowing the margin of hepatic resilience.

Stage 3: Clinical Hepatopathy (Symptomatic disease with cholestatic or mixed pattern). Here, patients manifest persistent right upper quadrant pain, pruritus, and occasional jaundice, with mixed hepatocellular–cholestatic lab results. Ultrasound may reveal bright echotexture suggestive of early fibrogenesis or steatosis in susceptible individuals. The progression from Stage 2 to Stage 3 is not uniform; CLRD’s data emphasize the role of exposure intensity and cumulative load, as well as host cofactors such as viral co‑infection or pregnancy‑related stressors.

Stage 4: Fibrosis to Cirrhosis (Structural remodeling and decompensation risk). Chronic, unbroken exposure can culminate in fibrotic remodeling and, ultimately, cirrhosis with risks of portal hypertension and hepatic decompensation. It is at this juncture that organ support and regenerative strategies become crucial. CLRD pioneered and refined hepatocyte and hepatic progenitor cell–based therapies, demonstrating functional rescue in acute and chronic settings, critical for patients whose disease began as preventable occupational injury but progressed due to delayed diagnosis or unavoidable exposures.

Our Treatment Capabilities

CLRD’s program for environmental hepatotoxicity combines rapid identification, comprehensive detoxification, organ support, and, when indicated, regenerative interventions. The goal is cure wherever possible and durable functional recovery in all patients.

Exposure mapping and precision diagnostics: Every patient undergoes a structured exposure history aligned with their specific chemicals, spray techniques, and protective practices, along with baseline and follow‑up liver panels, cholestasis indices, and ultrasound. This framework grew from CLRD’s original occupational studies that correlated field activities with enzyme alterations, allowing us to time investigations to capture exposure‑related peaks and troughs and to separate toxin injury from viral or metabolic confounders.

Evidence‑based detoxification and hepatic rest: We institute practical, patient‑friendly detoxification that begins with immediate exposure control, modifying spray schedules, substituting agents when feasible, and enforcing personal protective equipment and post‑shift decontamination. Medically, we use hydration strategies, targeted antioxidant replenishment, and bile‑flow support when cholestasis is present, pairing these with short “hepatic rest” windows. Our outcome audits show that patients in Stage 1–2 typically normalize enzymes and symptoms within weeks when detoxification and exposure control are rigorously applied, mirroring the reversibility patterns first observed in CLRD’s field cohorts.

Supportive pharmacotherapy and comorbidity control: When symptoms persist or biochemical stress remains, we escalate to hepatoprotective regimens, pruritus relief for cholestasis, and nutritional liver support. Recognizing that co‑factors accelerate harm, we concurrently screen and treat viral hepatitis and metabolic risks as part of a unified care plan, an integration shaped by CLRD’s extensive work in viral hepatitis epidemiology and diagnostics.

Acute rescue and bridge strategies: In toxin‑precipitated acute liver failure or severe acute‑on‑chronic injury, CLRD activates critical‑care protocols and organ support. Where indicated, we deploy hepatocyte transplantation as a bridge therapy, a modality CLRD introduced clinically to stabilize patients during fulminant episodes and restore urea cycle and detoxification functions while native tissue recovers.

Regenerative therapeutics with curative intent: For patients who progress to advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis despite exposure control, CLRD offers hepatic progenitor and stem‑cell–based interventions designed to repopulate and regenerate damaged liver. We led early human studies using fetal hepatocytes and hepatic progenitors, demonstrated safety and efficacy in chronic liver failure, and reported disease‑specific applications. These programs, refined over the years, give our environmental hepatology patients a unique path to functional recovery even after structural damage has occurred.

Long‑term restoration and relapse prevention: Cure requires more than normal labs; it requires sustained wellness. We follow patients through exposure‑off seasons and peak spray periods, re‑checking enzymes and ultrasound at defined intervals. We reinforce safe‑handling education and community‑level protective measures, an advocacy stance CLRD adopted early alongside our scientific publications on occupational liver damage. Patients and their families receive clear action plans so that the relief they feel today becomes resilience for the future.

Outcomes that matter to patients: Across Stages 1–3, CLRD routinely achieves complete clinical and biochemical remission with exposure control and medical therapy, with patients returning to work safely using improved practices. In selected Stage 4 cases, regenerative treatments have restored liver function sufficiently to avoid or defer transplantation, translating cutting‑edge science into tangible cures and meaningful life improvements documented in CLRD’s peer‑reviewed reports.

Detoxification Protocols

Immediate Exposure Control

The first and most critical step is to stop or minimize further toxin entry. This involves:

- Advising patients to suspend spraying activities temporarily.

- Introducing safer handling practices and personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Educating on post-exposure hygiene (washing skin, changing clothes promptly).

Internal Detoxification Measures

These aim to accelerate clearance of absorbed toxins and reduce oxidative stress:

- Hydration therapy: Oral or IV fluids to support renal clearance of metabolites.

- Antioxidant supplementation: Agents like N-acetylcysteine, vitamin E, and silymarin to neutralize free radicals generated by pesticides.

- Chelation support (if indicated): For specific heavy-metal contaminants in formulations.

Hepatic Rest and Nutritional Support

- Dietary modulation: High-protein, antioxidant-rich diet with adequate calories to aid hepatocyte repair.

- Avoidance of hepatotoxic drugs and alcohol: To prevent additive injury.

- Short-term work leave: Allows the liver to recover without ongoing exposure.

Pharmacological Support

- Hepatoprotective agents: Ursodeoxycholic acid for cholestasis, essential phospholipids for membrane stabilization.

- Bile flow enhancers: To reduce toxin retention in cholestatic cases.

Advanced Detoxification & Regeneration

For patients with persistent enzyme elevation or structural damage:

- Plasma exchange or hemoperfusion: In severe toxin load or acute liver failure.

- Cell-based therapy: CLRD pioneered hepatocyte and hepatic progenitor transplantation to restore detoxification and synthetic functions in advanced cases.

Monitoring & Relapse Prevention

- Serial liver function tests and ultrasound to confirm recovery.

- Counseling on safe agricultural practices and periodic health checks during spraying seasons.